Athens 1944: Britain’s dirty secret

When 28 civilians were killed in

Athens, it wasn’t the Nazis who were to blame, it was the British. Ed Vulliamy

and Helena Smith reveal how Churchill’s shameful decision to turn on the

partisans who had fought on our side in the war sowed the seeds for the rise of

the far right in Greece today

“I can still see it

very clearly, I have not forgotten,” says Títos Patríkios. “The Athens police

firing on the crowd from the roof of the parliament in Syntagma Square. The

young men and women lying in pools of blood, everyone rushing down the stairs

in total shock, total panic.”

And then came the

defining moment: the recklessness of youth, the passion of belief in a justice

burning bright: “I jumped up on the fountain in the middle of the square, the

one that is still there, and I began to shout: “Comrades, don’t disperse!

Victory will be ours! Don’t leave. The time has come. We will win!”

“I was,” he says

now, “profoundly sure, that we would win.” But there was no winning that day;

just as there was no pretending that what had happened would not change the

history of a country that, liberated from Adolf Hitler’s Reich barely six weeks

earlier, was now surging headlong towards bloody civil war.

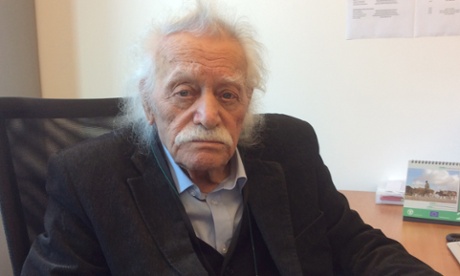

Even now, at 86,

when Patríkios “laughs at and with myself that I have reached such an age”, the

poet can remember, scene-for-scene, shot for shot, what happened in the central

square of Greek political life on the morning of 3 December 1944.

This was the day,

those 70 years ago this week, when the British army, still at war with Germany,

opened fire upon – and gave locals who had collaborated with the Nazis the guns

to fire upon – a civilian crowd demonstrating in support of the partisans with

whom Britain had been allied for three years.

The crowd carried

Greek, American, British and Soviet flags, and chanted: “Viva Churchill, Viva

Roosevelt, Viva Stalin’” in endorsement of the wartime alliance.

Twenty-eight

civilians, mostly young boys and girls, were killed and hundreds injured. “We

had all thought it would be a demonstration like any other,” Patríkios recalls.

“Business as usual. Nobody expected a bloodbath.”

Britain’s logic was

brutal and perfidious: Prime minister Winston Churchill considered the

influence of the Communist Party within the resistance movement he had backed

throughout the war – the National Liberation Front, EAM – to have grown

stronger than he had calculated, sufficient to jeopardise his plan to return

the Greek king to power and keep Communism at bay. So he switched allegiances

to back the supporters of Hitler against his own erstwhile allies.

There were others

in the square that day who, like the 16-year-old Patríkios, would go on to

become prominent members of the left. Míkis Theodorakis, renowned composer and

iconic figure in modern Greek history, daubed a Greek flag in the blood of

those who fell. Like Patríkios, he was a member of the resistance youth

movement. And, like Patríkios, he knew his country had changed. Within days,

RAF Spitfires and Beaufighters were strafing leftist strongholds as the Battle

of Athens – known in Greece as the Dekemvriana – began, fought

not between the British and the Nazis, but the British alongside supporters of

the Nazis against the partisans. “I can still smell the destruction,” Patríkios

laments. “The mortars were raining down and planes were targeting everything.

Even now, after all these years, I flinch at the sound of planes in war

movies.”

And thereafter

Greece’s descent into catastrophic civil war: a cruel and bloody episode in

British as well as Greek history which every Greek knows to their core –

differently, depending on which side they were on – but which remains curiously

untold in Britain, perhaps out of shame, maybe the arrogance of a lack of

interest. It is a narrative of which the millions of Britons who go to savour

the glories of Greek antiquity or disco-dance around the islands Mamma Mia-style, are unaware.

The legacy of this

betrayal has haunted Greece ever since, its shadow hanging over the turbulence

and violence that erupted in 2008 after the killing of a schoolboy by police –

also called the Dekemvriana – and created an abyss between the left and right

thereafter.

“The 1944 December

uprising and 1946-49 civil war period infuses the present,” says the leading

historian of these events, André Gerolymatos, “because there has never been a

reconciliation. In France or Italy, if you fought the Nazis, you were respected

in society after the war, regardless of ideology. In Greece, you found yourself

fighting – or imprisoned and tortured by – the people who had collaborated with

the Nazis, on British orders. There has never been a reckoning with that crime,

and much of what is happening in Greece now is the result of not coming to

terms with the past.”

Before the war,

Greece was ruled by a royalist dictatorship whose emblem of a fascist axe and

crown well expressed its dichotomy once war began: the dictator, General

Ioannis Metaxas, had been trained as an army officer in Imperial Germany, while

Greek King George II – an uncle of Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh – was

attached to Britain. The Greek left, meanwhile, had been reinforced by a huge

influx of politicised refugees and liberal intellectuals from Asia Minor, who

crammed into the slums of Pireaus and working-class Athens.

Both dictator and

king were fervently anti-communist, and Metaxas banned the Communist Party,

KKE, interning and torturing its members, supporters and anyone who did not

accept “the national ideology” in camps and prisons, or sending them into

internal exile. Once war started, Metaxas refused to accept Mussolini’s

ultimatum to surrender and pledged his loyalty to the Anglo-Greek alliance. The

Greeks fought valiantly and defeated the Italians, but could not resist the

Wehrmacht. By the end of April 1941, the Axis forces imposed a harsh occupation

of the country. The Greeks – at first spontaneously, later in organised groups

– resisted.

But, noted the

British Special Operations Executive (

Britain’s natural

allies were therefore EAM – an alliance of left wing and agrarian parties of

which the KKE was dominant, but by no means the entirety – and its partisan

military arm,

There is no overstating

the horror of occupation. Professor Mark Mazower’s book Inside Hitler’s Greece describes hideous bloccos or “round-ups” – whereby crowds

would be corralled into the streets so that masked informers could point out

By autumn 1944,

Greece had been devastated by occupation and famine. Half a million people had

died – 7% of the population.

On 12 October the

Germans evacuated Athens. Some

In and around the

European parliament in Brussels, the man in a Greek fisherman’s cap, with his

mane of white hair and moustache, stands out. He is Manolis

Glezos, senior MEP for the leftist Syriza party of Greece.

Glezos is a man of

humbling greatness. On 30 May 1941, he climbed the Acropolis with another

partisan and tore down the swastika flag that had been hung there a month

before. He was arrested by the Gestapo in 1942, was tortured and as a result

suffered from tuberculosis. He escaped and was re-arrested twice – the second

time by collaborators. He recalls being sentenced to death in May 1944, before

the Germans left Athens – “They told me my grave had already been dug”. Somehow

he avoided execution and was then saved from a Greek courtmartial’s firing

squad during the civil war period by international outcry led by General de

Gaulle, Jean-Paul Sartre and the Archbishop of Canterbury, the Rev Geoffrey

Fisher.”

Seventy years

later, he is an icon of the Greek left who is also hailed as the greatest

living authority on the resistance. “The English, to this day, argue that they

liberated Greece and saved it from communism,” he says. “But that is the basic

problem. They never liberated Greece. Greece had been liberated by the

resistance, groups across the spectrum, not just EAM, on 12 October. I was

there, on the streets – people were everywhere shouting: ‘Freedom!’ we cried, Laokratia! – ‘Power to the People!’”

The British duly

arrived on 18 October, installed a provisional government under Georgios

Papandreou and prepared to restore the king. “From the moment they came,”

recalls Glezos, “the people and the resistance greeted them as allies. There

was nothing but respect and friendship towards the British. We had no idea that

we were already giving up our country and our rights.” It was only a matter of

time before EAM walked out of the provisional government in frustration over

demands that the partisans demobilise. The negotiations broke down on 2

December.

Official British

thinking is reflected in War Cabinet papers and other documents kept in the

Public Record Office at Kew. As far back as 17 August 1944, Churchill had

written a “Personal and Top Secret” memo to US president Franklin Roosevelt to

say that: “The War Cabinet and Foreign Secretary are much concerned about what

will happen in Athens, and indeed Greece, when the Germans crack or when their

divisions try to evacuate the country. If there is a long hiatus after German

authorities have gone from the city before organised government can be set up,

it seems very likely that EAM and the Communist extremists will attempt to

seize the city.”

But what the

freedom fighters wanted, insists Glezos “was what we had achieved during the

war: a state ruled by the people for the people. There was no plot to take over

Athens as Churchill always maintained. If we had wanted to do that, we could

have done so before the British arrived.” During November, the British set

about building the new National Guard, tasked to police Greece and disarm the

wartime militias. In reality, disarmament applied to

In conversation,

Gerolymatos says: “So far as

Any British notion

that the Communists were poised for revolution fell within the context of the

so-called Percentages Agreement, forged between Churchill and Soviet Commissar

Josef Stalin at the code-named “Tolstoy Conference” in Moscow on 9 October

1944. Under the terms agreed in what Churchill called “a naughty document”,

southeast Europe was carved up into “spheres of influence”, whereby – broadly –

Stalin took Romania and Bulgaria, while Britain, in order to keep Russia out of

the Mediterranean, took Greece. The obvious thing to have done, argues

Gerolymatos, “would have been to incorporate

“But the British

and the Greek government in exile decided from the outset that

Meanwhile,

continues Gerolymatos: “The Greek communists had decided not to try to take

over the country, as least not until late November/early December 1944. The KKE

wanted to push for a left-of-centre government and be part of it, that’s all.”

Echoing Glezos, he says: “If they had wanted a revolution, they would not have

left 50,000 armed men outside the capital after liberation – they’d have

brought them in.”

“By recruiting the

collaborators, the British changed the paradigm, signalling that the old order

was back. Churchill wanted the conflict,” says Gerolymatos. “We must remember:

there was no Battle for Greece. A large number of the British troops that

arrived were administrative, not line units. When the fighting broke out in

December, the British and the provisional government let the Security

Battalions out of Goudi; they knew how to fight street-to-street because they’d

done it with the Nazis. They’d been fighting

The morning of Sunday

3 December was a sunny one, as several processions of Greek republicans,

anti-monarchists, socialists and communists wound their way towards Syntagma

Square. Police cordons blocked their way, but several thousand broke through;

as they approached the square, a man in military uniform shouted: “Shoot the

bastards!” The lethal fusillade – from Greek police positions atop the

parliament building and British headquarters in the Grande Bretagne hotel –

lasted half an hour. By noon, a second crowd of demonstrators entered the

square, until it was jammed with 60,000 people. After several hours, a column

of British paratroops cleared the square; but the Battle of Athens had begun,

and Churchill had his war.

Manolis Glezos was

sick that morning, suffering from tuberculosis. “But when I heard what had

happened, I got off my sick bed,” he recalls. The following day, Glezos was

roaming the streets, angry and determined, disarming police stations. By the

time the British sent in an armoured division he and his comrades were waiting.

“I note the fact,”

he says, “that they would rather use those troops to fight our population than

German Nazis!” By the time British tanks rolled in from the port of Pireaus, he

was lying in wait: “I remember them coming up the Sacred Way. We were dug in a

trench. I took out three tanks,” he says. “There was much bloodshed, a lot of

fighting, I lost many very good friends. It was difficult to strike at an

Englishman, difficult to kill a British soldier – they had been our allies. But

now they were trying to destroy the popular will, and had declared war on our

people”.

At battle’s peak,

Glezos says, the British even set up sniper nests on the Acropolis. “Not even

the Germans did that. They were firing down on EAM targets, but we didn’t fire

back, so as not [to harm] the monument.”

On 5 December, Lt

Gen Scobie imposed martial law and the following day ordered the aerial bombing

of the working-class Metz quarter. “British and government forces,” writes

anthropologist Neni Panourgia in her study of families in that time, “having at

their disposal heavy armament, tanks, aircraft and a disciplined army, were

able to make forays into the city, burning and bombing houses and streets and

carving out segments of the city… The German tanks had been replaced by British

ones, the SS and Gestapo officers by British soldiers.” The house belonging to

actor Mimis Fotopoulos, she

writes, was burned out with a portrait of Churchill above the fireplace.

“I recall shouting

slogans in English, during one battle in Koumoundourou Square because I had a

strong voice and it was felt I could be heard,” says poet Títos Patríkios as we

talk in his apartment. “‘We are brothers, there’s nothing to divide us, come

with us!’ That’s what I was shouting in the hope that they [British troops]

would withdraw. And right at that moment, with my head poked above the wall, a

bullet brushed over my helmet. Had I not been yanked down by Evangelos

Goufas[another poet], who was there next to me, I would have been dead.”

He can now smile at

the thought that only months after the killing in the square he was back at

school, studying English on a British Council summer course. “We were enemies,

but at the same time friends. In one battle I came across an injured English soldier

and I took him to a field hospital. I gave him my copy of Robert Louis

Stevenson’s Kidnapped which I

remember he kept.”

It is illuminating

to read the dispatches by British soldiers themselves, as extracted by the head

censor, Capt JB Gibson, now stored at the Public Record Office. They give no

indication that the enemy they fight was once a partisan ally, indeed many

troops think they are fighting a German-backed force. A warrant officer writes:

“Mr Churchill and his speech bucked us no end, we know now what we are fighting

for and against, it is obviously a Hun element behind all this trouble.” From

“An Officer”: “You may ask: why should our boys give their lives to settle

Greek political differences, but they are only Greek political differences? I say:

no, it is all part of the war against the Hun, and we must go on and

exterminate this rebellious element.”

Cabinet papers at

Kew trace the reactions in London: a minute of 12 December records Harold

Macmillan, political advisor to Field Marshal Alexander, returning from Athens

to recommend “a proclamation of all civilians against us as rebels, and a

declaration those found in civilian clothes opposing us with weapons were

liable to be shot, and that 24 hours notice should be given that certain areas

were to be wholly evacuated by the civilian population” – ergo, the British

Army was to depopulate and occupy Athens. Soon, reinforced British troops had

the upper hand and on Christmas Eve Churchill arrived in the Greek capital in a

failed bid to make peace on Christmas Day.

“I will now tell

you something I have never told anyone,” says Manolis Glezos mischievously. On

the evening of 25 December Glezos would take part in his most daring escapade,

laying more than a ton of dynamite under the hotel Grande Bretagne, where Lt

Gen Scobie had headquartered himself. “There were about 30 of us involved. We

worked through the tunnels of the sewerage system; we had people to cover the

grid-lines in the streets, so scared we were that we’d be heard. We crawled

through all the shit and water and laid the dynamite right under the hotel,

enough to blow it sky high.

“I carried the fuse

wire myself, wire wound all around me, and I had to unravel it. We were

absolutely filthy, covered [in excrement] and when we got out of the sewerage

system I remember the boys washing us down. I went over to the boy with the

detonator; and we waited, waited for the signal, but it never came. Nothing.

There was no explosion. Then I found out: at the last minute EAM found out that

Churchill was in the building, and put out an order to call off the attack.

They’d wanted to blow up the British command, but didn’t want to be responsible

for assassinating one of the big three.”

At the end of the

Dekemvriana, thousands had been killed; 12,000 leftists rounded up and sent to

camps in the Middle East. A truce was signed on 12 February, the only clause of

which that was even partially honoured was the demobilisation of

Títos Patríkios is

not the kind of man who wants the past to impinge on the present. But he does

not deny the degree to which this history has done just that – affecting his

poetry, his movement, his quest to find “le mot juste”. This most measured and

mild-mannered of men would spend years in concentration camps, set up with the

help of the British as civil war beckoned. With imprisonment came hard labour,

and with hard labour came torture, and with exile came censorship. “The first

night on Makronissos [the most infamous camp] we were all beaten very badly.

“I spent six months

there, mostly breaking stones, picking brambles and carrying sand. Once, I was

made to stand for 24 hours after it had been discovered that a newspaper had

published a letter describing the appalling conditions in the camp. But though

I had written it, and had managed to pass it on to my mother, I never admitted

to doing so and throughout my time there I never signed a statement of

repentance.”

Patríkios was among

the relatively fortunate; thousands of others were executed, usually in public,

their severed heads or hanging bodies routinely displayed in public squares.

His Majesty’s embassy in Athens commented by saying the exhibition of severed

heads “is a regular custom in this country which cannot be judged by western

European standards”.

The name of the man

in command of the “British Police Mission” to Greece is little known. Sir

Charles Wickham had been assigned by Churchill to oversee the new Greek

security forces – in effect, to recruit the collaborators. Anthropologist Neni

Panourgia describes Wickham as “one of the persons who traversed the empire

establishing the infrastructure needed for its survival,” and credits him with

the establishment of one of the most vicious camps in which prisoners were

tortured and murdered, at Giaros.

From Yorkshire,

Wickham was a military man who served in the Boer War, during which

concentration camps in the modern sense were invented by the British. He then

fought in Russia, as part of the allied Expeditionary Force sent in 1918 to aid

White Russian Czarist forces in opposition to the Bolshevik revolution. After

Greece, he moved on in 1948 to Palestine. But his qualification for Greece was

this: Sir Charles was the first Inspector General of the Royal Ulster

Constabulary, from 1922 to 1945.

The RUC was founded

in 1922, following what became known as the Belfast pogroms of 1920-22, when

Catholic streets were attacked and burned. It was, writes the historian Tim Pat

Coogan, “conceived not as a regular police body, but as a counter-insurgency

one… The new force contained many recruits who joined up wishing to be ordinary

policemen, but it also contained murder gangs headed by men like a head

constable who used bayonets on his victims because it prolonged their agonies.”

As the writer

Michael Farrell found out when researching his book Arming the Protestants, much material pertaining to Sir

Charles’s incorporation of these UVF and Special Constabulary militiamen into

the RUC has been destroyed, but enough remains to give a clear indication of

what was happening. In a memo written by Wickham in November 1921, before the

formation of the RUC, and while the partition treaty of December that year was

being negotiated, he had addressed “All County Commanders” as follows: “Owing

to the number of reports which has been received as to the growth of

unauthorised loyalist defence forces, the government have under consideration

the desirability of obtaining the services of the best elements of these

organisations.”

Coogan, Ireland’s

greatest and veteran historian, stakes no claim to neutrality over matters

concerning the Republic and Union, but historical facts are objective and he

has a command of those that none can match. We talk at his home outside Dublin

over a glass of whiskey appositely called “Writer’s Tears”.

“It’s the narrative

of empire,” says Coogan, “and, of course, they applied it to Greece. That same

combination of concentration camps, putting the murder gangs in uniform, and

calling it the police. That’s colonialism, that’s how it works. You use

whatever means are necessary, one of which is terror and collusion with

terrorists. It works.

“Wickham organised

the RUC as the armed wing of Unionism, which is something it remained

thereafter,” he says. “How long was it in the history of this country before

the Chris Patten report of 1999, and Wickham’s hands were finally prised off

the police? That’s a hell of a long piece of history – and how much suffering,

meanwhile?”

The head of MI5

reported in 1940 that “in the personality and experience of Sir Charles

Wickham, the fighting services have at their elbow a most valuable friend and

counsellor”. When the intelligence services needed to integrate the Greek

Security Battalions – the Third Reich’s “Special Constabulary” – into a new

police force, they had found their man.

Greek academics

vary in their views on how directly responsible Wickham was in establishing the

camps and staffing them with the torturers. Panourgia finds the camp on Giaros

– an island which even the Roman Emperor Tiberius decreed unfit for prisoners –

to have been Wickham’s own direct initiative. Gerolymatos, meanwhile, says:

“The Greeks didn’t need the British to help them set up camps. It had been done

before, under Metaxas.” Papers at Kew show British police serving under Wickham

to be regularly present in the camps.

Gerolymatos adds:

“The British – and that means Wickham – knew who these people were. And that’s

what makes it so frightening. They were the people who had been in the torture

chambers during occupation, pulling out the fingernails and applying

thumbscrews.” By September 1947, the year the Communist Party was outlawed,

19,620 leftists were held in Greek camps and prisons, 12,000 of them in

Makronissos, with a further 39,948 exiled internally or in British camps across

the Middle East. There exist many terrifying accounts of torture, murder and

sadism in the Greek concentration camps – one of the outrageous atrocities in

postwar Europe. Polymeris Volgis of New York University describes how a system

of repentance was introduced as though by a “latter-day secular Inquisition”,

with confessions extracted through “endless and violent degradation”.

Women detainees

would have their children taken away until they confessed to being “Bulgarians”

and “whores”. The repentance system led Makronissos to be seen as a “school”

and “National University” for those now convinced that “Our life belongs to

Mother Greece,’ in which converts were visited by the king and queen, ministers

and foreign officials. “The idea”, says Patríkios, who never repented, “was to reform

and create patriots who would serve the homeland.”

Minors in the

Kifissa prison were beaten with wires and socks filled with concrete. “On the

boys’ chests, they sewed name tags”, writes Voglis, “with Slavic endings added

to the names; many boys were raped”. A female prisoner was forced, after a

severe beating, to stand in the square of Kastoria holding the severed heads of

her uncle and brother-in-law. One detainee at Patras prison in May 1945 writes

simply this: “They beat me furiously on the soles of my feet until I lost my

sight. I lost the world.”

Manolis Glezos has

a story of his own. He produces a book about the occupation, and shows a

reproduction of the last message left by his brother Nikos, scrawled on the

inside of a beret. Nikos was executed by collaborators barely a month before

the Germans evacuated Greece. As he was being driven to the firing squad, the

19-year-old managed to throw the cap he was wearing from the window of the car.

Subsequently found by a friend and restored to the family, the cap is among

Glezos’s most treasured possessions.

Scribbled inside,

Nikos had written: “Beloved mother. I kiss you. Greetings. Today I am going to

be executed, falling for the Greek People. 10-5-44.”

Nowhere else in

newly liberated Europe were Nazi sympathisers enabled to penetrate the state

structure – the army, security forces, judiciary – so effectively. The

resurgence of neo-fascism in the form of present-day far-right party Golden

Dawn has direct links to the failure to purge the state of right-wing

extremists; many of Golden Dawn’s supporters are descendants of Battalionists,

as were the “The Colonels” who seized power in 1967.

Glezos says: “I

know exactly who executed my brother and I guarantee they all got off

scot-free. I know that the people who did it are in government, and no one was

ever punished.” Glezos has dedicated years to creating a library in his

brother’s honour. In Brussels, he unabashedly asks interlocutors to contribute

to the fund by popping a “frango” (a euro) into a silk purse. It is, along with

the issue of war reparations, his other great campaign, his last wish: to erect

a building worthy of the library that will honour Nikos. “The story of my

brother is the story of Greece,” he says.

There is no claim

that

In December 1946,

Greek prime minister Konstantinos Tsaldaris, faced with the probability of

British withdrawal, visited Washington to seek American assistance. In

response, the US State Department formulated a plan for military intervention

which, in March 1947, formed the basis for an announcement by President Truman

of what became known as the Truman

Doctrine, to intervene with force wherever communism was considered a

threat. All that had passed in Greece on Britain’s initiative was the first

salvo of the Cold War.

Glezos still calls

himself a communist. But like Patríkios, who rejected Stalinism, he believes

that communism, as applied to Greece’s neighbours to the north, would have been

a catastrophe. He recalls how he even gave Nikita Khrushchev, the Soviet leader

who would de-Stalinise the Soviet Union “an earful about it all”. The occasion

arose when Khrushchev invited Glezos – who at the height of the Cold War was a

hero in the Soviet Union, honoured with a postage stamp bearing his image – to

the Kremlin. It was 1963 and Khrushchev was in talkative mood. Glezos wanted to

know why the Red Army, having marched through Bulgaria and Romania, stopped at

the Greek border. Perhaps the Russian leader could explain.

“He looked at me

and said, ‘Why?’

“I said: ‘Because

Stalin didn’t behave like a communist. He divided up the world with others and

gave Greece to the English.’ Then I told him what I really thought, that Stalin

had been the cause of our downfall, the root of all evil. All we had wanted was

a state where the people ruled, just like our [then] government in the

mountains, where you can still see the words ‘all powers spring from the people

and are executed by the people’ inscribed into the hills. What they wanted, and

created, was rule by the party.”

Khrushchev, says

Glezos, did not openly concur. “He sat and listened. But then after our meeting

he invited me to dinner, which was also attended by Leonid Brezhnev [who

succeeded Khrushchev in 1964] and he listened for another four and a half

hours. I have always taken that for tacit agreement.”

For Patríkios, it

was not until the Soviet invasion of Hungary in 1956, that the penny dropped: a

line had been drawn across the map, agreed by Churchill and Stalin. “When I saw

the west was not going to intervene [during the Budapest uprising] I realised what

had happened – the agreed ‘spheres of influence’. And later, I understood that

the Dekemvriana was not a local conflict, but the beginning of the Cold War

that had started as a warm war here in Greece.”

Patríkios returned

to Athens as a detainee “on leave” and was eventually granted a passport in

1959. Upon procuring it, he immediately got on a ship to Paris where he would

spend the next five years studying sociology and philosophy at the Sorbonne.

“In politics there are no ethics,” he says, “especially imperial politics.”

It’s the afternoon

of 25 January 2009. The tear gas that has drenched Athens – a new variety,

imported from Israel – clears. A march in support of a Bulgarian cleaner, whose

face has been disfigured in an acid attack by neo-fascists, has been broken up

by riot police after hours of street-fighting.

Back in the

rebel-held quarter of Exarcheia, a young woman called Marina pulls off her

balaclava and draws air. Over coffee, she answers the question: why Greece? Why

is it so different from the rest of Europe in this regard – the especially

bitter war between left and right? “Because,” she replies, “of what was done to

us in 1944. The persecution of the partisans who fought the Nazis, for which

they were honoured in France, Italy, Belgium or the Netherlands – but for

which, here, they were tortured and killed on orders from your government.”

She continues: “I

come from a family that has been detained and tortured for two generations

before me: my grandfather after the Second World War, my father under the Junta

of the colonels – and now it could be me, any day now. We are the grandchildren

of the andartes, and our

enemies are Churchill’s Greek grandchildren.”

“The whole thing”,

spits Dr Gerolymatos, “was for nothing. None of this need have happened, and

the British crime was to legitimise people whose record under occupation by the

Third Reich put them beyond legitimacy. It happened because Churchill believed

he had to bring back the Greek king. And the last thing the Greek people wanted

or needed was the return of a de-frocked monarchy backed by Nazi collaborators.

But that is what the British imposed, and it has scarred Greece ever since.”

“All those

collaborators went into the system,” says Manilos Glezos. “Into the government

mechanism – during and after the civil war, and their sons went into the

military junta. The deposits remain, like malignant cells in the system.

Although we liberated Greece, the Nazi collaborators won the war, thanks to the

British. And the deposits remain, like bacilli in the system.”

But there is one

last thing Glezos would like to make clear. “You haven’t asked: ‘Why do I go

on? Why I am doing this when I am 92 years and two months old?’ he says, fixing

us with his eyes. “I could, after all, be sitting on a sofa in slippers with my

feet up,” he jests. “So why do I do this?”

He answers himself:

“You think the man sitting opposite you is Manolis but you are wrong. I am not

him. And I am not him because I have not forgotten that every time someone was

about to be executed, they said: ‘Don’t forget me. When you say good morning,

think of me. When you raise a glass, say my name.’ And that is what I am doing

talking to you, or doing any of this. The man you see before you is all those

people. And all this is about not forgetting them.”

Timeline:

the battle between left and right

Late summer 1944 German forces withdraw from most of Greece, which is

taken over by local partisans. Most of them are members of

October 1944 Allied forces, led by General Ronald Scobie, enter Athens, the last

German-occupied area, on 13 October. Georgios Papandreou returns from exile

with the Greek government

2 December 1944 Rather than integrate

3 December 1944 Violence in Athens after 200,000 march against the

demands. More than 28 are killed and hundreds are injured. The 37-day

Dekemvrianá begins. Martial law is declared on 5 December

January/February 1945 Gen Scobie agrees to a ceasefire in exchange for

1945/46 Right-wing gangs kill more than 1,100 civilians, triggering civil war when

government forces start battling the new Democratic Army of Greece (DSE),

mainly former

1948-49 DSE suffers a catastrophic defeat in the summer of 1948, with nearly

20,000 killed. In July 1949 Tito closes the Yugoslav border, denying DSE

shelter. Ceasefire signed on 16 October 1949

21 April 1967 Right-wing forces seize power in a coup d’état. The junta lasts until

1974. Only in 1982 are communist veterans who had fled overseas allowed to

return to Greece